spirituality

genetics

The Cure: continued /6

When they had circled the village and returned to the Place de l'Eglise, le Père led them proudly round the side of the Church, not quite as far as the toilettes, where stood his three workmen, beaming proudly by a large tarpaulin over something bulky. They whipped off the tarpaulin as the procession approached, to reveal, at one end of the municipal flowerbed by the side of the church, a faux stone basin (the biggest available at the local garden centre) and a plinth. There was a huge cheer when, after Sainte Anne had been manoeuvred onto her plinth, le Père pressed a button and a fountain sprang up before her.

— It is my gift to the village, said le Père. — The new fountain of Sainte Anne!

After the applause had died down, he continued: —The fountain has only the water of the water company, so there is nothing miraculous about it, but this was not always the case here at our fine Eglise Sainte Anne. In the last century there were many miracles reported here, including the cure of blindness.

He had never had such a congregation for a sermon before, and he made the most of it, with a carefully prepared speech about the miraculous being possible — a Pardon in a week! — and the necessity to bring back the spiritual into the lives of ourselves, each other, and the community. He kept it short, and did not labour his points. Those at the back of the crowd were distracted by the sounds of the bagpipes and the bombarde tuning up for the concert and dance exhibition to come.

The dances were colourful and traditional. Les Sonneurs played, and the men and women

in their costumes bobbed and danced in lines and circles. Mademoiselle Franchard's

boyfriend Girard, bearded and resplendent in full costume, called out the names of the

dances — the gavotte, an dro, hanter dro, laridé and dañs plinn, figure dances such

as the jabadao, pach-pi and bals and some whirling couple dances. But they ended with

everyone joining in, lines and lines of dancers bobbing up and down. Les sonneurs, the

Breton dancers, the schoolchildren, Madame Céline and her coterie, the acolyte Yves and

his mother, M. Barnard and his family, even Madame Ségale and all the rest of the village

people, with the visitors, the English family and the tourists, all dancing in a huge line

that stretched right round the church and the Place de l'Eglise and out onto the road. And

in the middle danced Père Benoît, with unsuspected resources of energy, dancing and

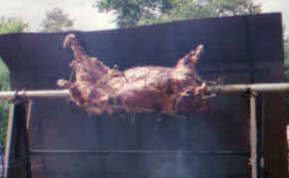

dancing, until they danced all the way down to the playing field for the Fest Noz  , and the local cider that was barely alcoholic, if at all, and the ox

roast and more dancing, and music, and singing. By the time he went to bed, Père Benoît

was too tired to notice who brought him home.

, and the local cider that was barely alcoholic, if at all, and the ox

roast and more dancing, and music, and singing. By the time he went to bed, Père Benoît

was too tired to notice who brought him home.

Le Journal de l'Ouest devoted a whole page to pictures of the Pardon. There was also an article about the miraculous well of Saint Anne.

The reporter had interviewed a professor at the University of Rennes who told the story of a family Faubert, parishioners of a predecessor of Père Benoît. A mutation in the genes of Grandmère Marie Faubert, a hundred and fifty years ago, had caused many of her descendants to suffer from a form of inherited glaucoma. The unfortunate ones brought their children to be blessed at their parish well of St. Anne, in the hope that they would not develop the affliction. The number of blessings thus performed to ward off eye disease led to the well acquiring a reputation for curing blindness. So started the legend. There were no miracles, after all.

Le Père did not bother to read on. He was already beginning to plan the Pardon for next year. If he could achieve all that he had achieved in only a week (—Dieu merci! he whispered, hastily), then what could he not achieve in twelve months?

The End

Part of this work was submitted as the Dissertation for the MA in Writing

at

Nottingham Trent University